Program Notes — UNFINISHED BRUCKNER

Leave a Comment

Unfinished Nobility

A special corner of the repertory is reserved for those works that are highly valued despite (or because of) being left incomplete by their authors. It’s quite the honor roll: Bach’s The Art of Fugue, Mozart’s Requiem and C Minor Mass, Mahler’s Tenth Symphony. To that we can add the two most tantalizing of all: Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony No. 8, and Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9, left incomplete at Bruckner’s death.

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

Symphony No. 8 in B Minor “Unfinished” D. 759 (1822)

The “Unfinished” symphony barely escaped oblivion. In 1822 Schubert sent the first two movements – all he ever completed – to his friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner in Graz. At that point the manuscript disappeared for 40 years, only to reappear in 1865 when the now elderly Hüttenbrenner gave the manuscript to conductor Johann von Herbeck, who lost no time bringing this remarkable torso of a symphony to the world’s attention.

“Every heart rejoiced,” exclaimed critic Eduard Hanslick of the December 1865 premiere, “as if, after a long separation, the composer himself were amongst us in person.” If so, then the Franz Schubert there in person was most indubitably not the cherubic little guy already being typecast as chronically lovesick and misunderstood. ThisFranz Schubert was a brooding Romantic, downright Byronic in his volatile moods, master of symphonic form and orchestration, and the resurrected Eighth Symphony was an exponential advance over his earlier symphonies.

Which makes it all the more of a shame that it isn’t finished. Nobody really knows why. Theories have been floated, of course, just as completions have been offered. The only thing that can be said with any certainty is that Schubert definitely did mean to finish it. The first movement opens in a darkness that is broken only fitfully by patches of light – the familiar second theme, for example – but on the whole it sustains a sense of Gothic gloom throughout. In the tender, lyrical second movement, Schubert the master orchestrator gives prevalent solos to both clarinet and horn, both instruments often associated with “romantic” moods.

Anton Bruckner (1824–1896)

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor (1894–96)

Nowadays it’s easy to get to Ansfelden, Austria. Just take the A1 westbound out of Vienna and after a while Ansfelden will be on your left, immediately following the exit for central Linz. Ansfelden turns out to be a prosperous residential suburb basking in that comfortable family-oriented middle-class lifestyle familiar throughout the developed modern world.

Anton Bruckner was born in an Ansfelden that was an impoverished rural hamlet with more cows than people and shortages of food and decent jobs. It must have seemed like the end of nowhere to a talented young chap like Anton Bruckner, son of a village schoolmaster. His father got him started in music, then in his early teens he was sent off to the nearby Augustinian monastery of Sankt Florian, where he became the organist, then ditto in nearby Linz.

It was a quiet, unassuming life. In 1868 he relocated to teach at the Vienna Conservatory and things got a lot more complicated. The shy and unsophisticated Bruckner, a village and monastery man down to his toes, was a poor fit for Vienna’s toxic musical politics. But he persisted amidst a steady barrage of critical attacks, continued to produce luxuriantly epic symphonies, and eventually found a certain measure of success with Viennese musicians and their notoriously fickle public. He stayed unmarried – not for lack of trying – and died in his humble but comfortable Vienna apartment at the age of 72. It took a while for posterity to catch on, but catch on it did and nowadays Bruckner enjoys an enviable reputation as a supreme master of the late Romantic symphony. His music even survived being appropriated by the Nazis, a tribute indeed to its fundamental nobility and goodness.

Bruckner began work on what turned out to be his last symphony in 1887, but it wasn’t long before he became sidelined on revisions of several of his earlier symphonies. As of 1894 he was still making sporadic progress, and by 1896 he had completed the first three movements.

And that’s where it stopped. Bruckner died on October 11, 1896 with the third-movement Adagio finished after numerous false starts, revisions, and retries. One of his friends, Ferdinand Löwe, prepared a performing version of the three-movement symphony for its official premiere in 1903, but Löwe couldn’t resist tinkering with Bruckner’s original, very much to the symphony’s detriment. It wasn’t until 1932 that the world finally heard the Ninth as Bruckner intended it. Since then, there have been numerous attempts at re-creating a fourth movement, but all dwell in the realm of speculation, no matter how well-founded their intentions. The Ninth, as Bruckner handed it down to posterity, is a three-movement symphony.

But what a three movements! Vast, brooding, powerful, exultant, introspective, menacing, comforting … the list of descriptive adjectives is more or less endless. The Bruckner Ninth offers a musical demonstration of the old parable of the blind men and the elephant – each comes to a different conclusion about what’s actually there, depending on which part of the elephant he’s feeling. The first movement begins much like Beethoven’s Ninth symphony, with a sense of the very creation of it all taking place before us. It makes its way with all due majesty through at least three main themes and great spans of developmental action before concluding in an almost overwhelming wall of sound.

The second movement, on the other hand, is a fiery scherzo, its searing demeanor slightly ameliorated by a gentler interlude that makes a game attempt at playfulness but is soon engulfed in the overriding turbulence. Then comes the Adagio finale, a sustained essay in ecstatic radiance interrupted by angst-ridden outbursts. It ends as it can only end for this most spiritually-aware of composers, with a sense of calm acceptance and consolation.nephew Vladimir ‘Bob’ Davydov, “and I love it as I have never before loved one of my musical offspring.”

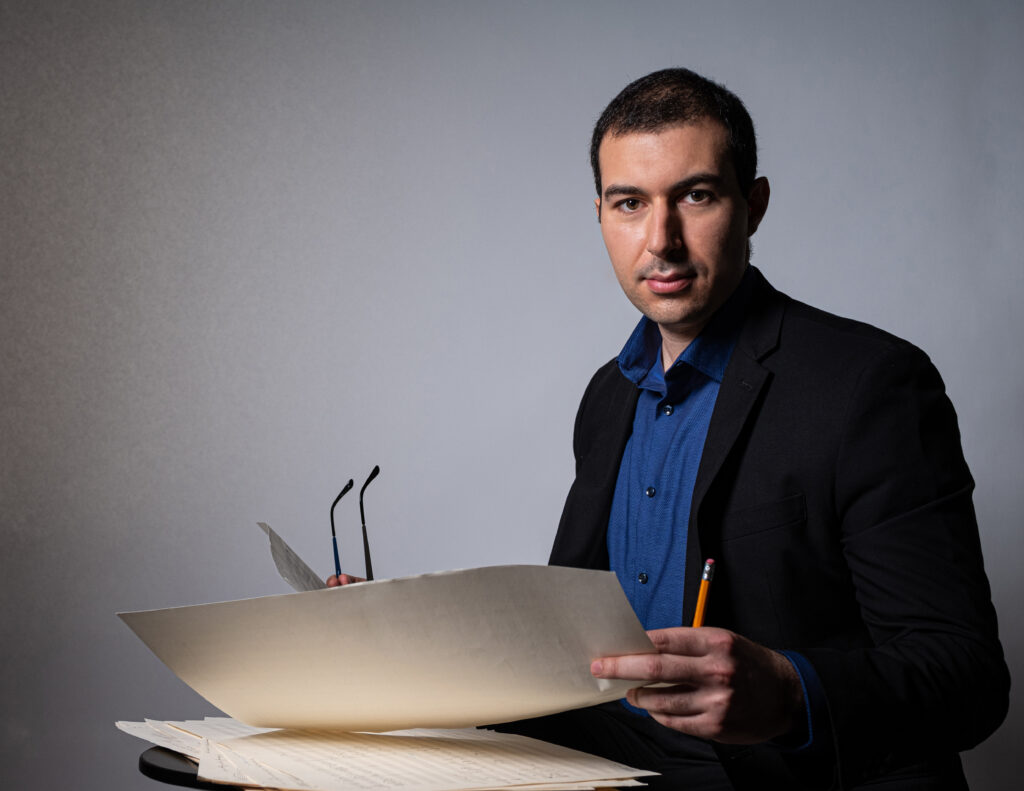

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

The 24-25 CROWNING ACHIEVEMENTS Season concludes with UNFINISHED BRUCKNER, on Saturday, May 3 at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, May 4 at 4 p.m. at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Single tickets start at $50 and at $25 for students 25 and under, and include a free 30-minute pre-concert talk starting one hour before the performance. Buy tickets online or call or visit the Lesher Center Ticket Office at 925.943.7469, Wed – Sun, 12:00 noon to 6:00 p.m.