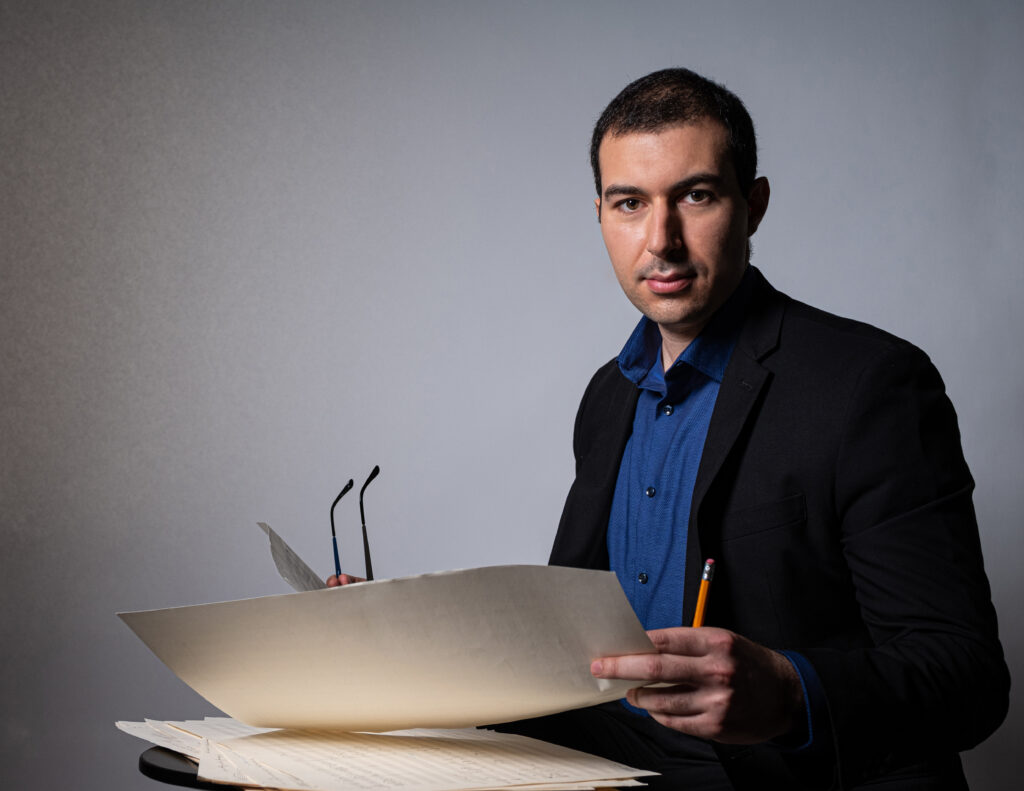

Saad Haddad (b. 1992)

Mishwar (World Premiere, 2024)

Saad Haddad, the California Symphony’s current Resident Composer, is acclaimed for his distinctive blend of Western art music and Middle Eastern idioms. Haddad has drawn Mishwar (Arabic مشوار(, meaning “A Trip,” out of his own memories. He tells us that:

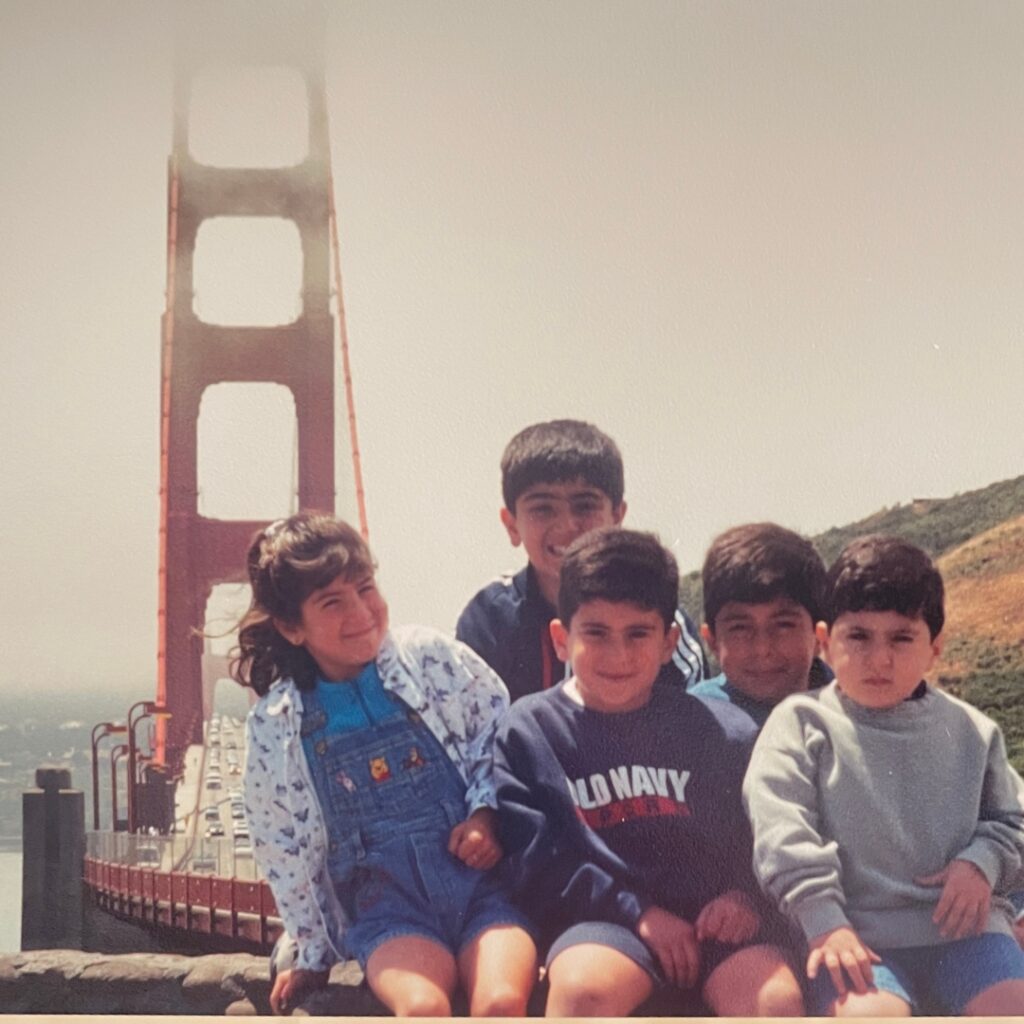

“Throughout my childhood, my family and I made frequent trips up the coast of California, from the San Fernando Valley up to the Bay Area. Awaiting us there was the paternal, Jordanian side of my rambunctious, extended family, who we always looked forward to seeing again. Near the five-hour mark of each trip, like clockwork, a waft of garlic would whisk itself into our car, signaling both the impending arrival to our final destination, San Jose, and the start of what my two younger brothers and I would infamously call “the Arabic game.”

“Once we made our way through Gilroy, my dad, on cue, liked to see who retained the most out of the Arabic language among the three of us, who were all born in the U.S.: “What color is that car?”; “Who can count to 20?”; “How do you say ‘sky’?”; and so on. None of us were quite good at this game, though the moments when one of us would remember a word or phrase would always bring joy for my dad.’”

Mishwar is a commission by the California Symphony, and receives its world premiere performance in these concerts. Haddad describes it as “a conversation, albeit quite a loud one, between both my identities: a coastal American trained in Western classical music, and the son of Jordanian and Lebanese immigrants attempting to retain the culture they themselves grew up in.”

Clara Schumann (1819–1896)

Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in A Minor, Op. 7 (1836)

It’s true enough that Friedrich Wieck merits a place amongst music history’s villains, but it’s also true enough that, from his point of view, he was really, really trying to do the right thing.

That right thing was protecting his precious daughter Clara from a suitor who qualified as every father’s dreaded Boyfriend from Hell. Robert Schumann was actually one of Friedrich’s piano students, but as of the 1830s he was nobody’s idea of good husband material. He had practically no career prospects. He was a lousy pianist. He drank way too much. His mental stability was a matter of concern. And that aforesaid precious daughter Clara Wieck? She was most immeasurably gifted with the Right Stuff, by her early teens already an admired pianist with a marked flair for composition. And Friedrich Wieck had made her that way.

Papa’s howls of protest and legalistic skulduggery notwithstanding, Clara married Robert the minute she reached the age of consent. She made her choices, became one of history’s supreme pianists, and focused on Robert’s compositions rather than her own. What we have—and it isn’t much—of Clara Schumann’s music is worth exploring and hearing again and again.

Her Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in A Minor, Op. 7 would be impressive enough had it been merely the work of a 16-year old. But Clara actually wrote what became the Finale when she was 13. Undoubtedly the concerto’s most delectable part is the slow movement, a Romanze that spins out a long-lined melody in the solo piano that’s eventually joined by a cello in an ingratiating duet. But the whole is a pleasure, from its well-ordered first movement to its dynamic and extroverted finale.

Johannes Brahms (1833–1897)

Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 (1876)

“I will never compose a symphony! You have no idea how disheartening it is for us to hear such a great giant marching behind,” griped Johannes Brahms to conductor Hermann Levi. Brahms wasn’t the only composer active in the mid-nineteenth century suffering from a severe case of Beethoven Envy. The newly founded municipal orchestras were doing their best to satisfy a deep public yen for the Beethoven symphonies—up to then largely inaccessible to most music lovers—and in their zeal had brought about an unfortunate side effect: the symphony had been effectively killed off as a living genre. Before 1850 both Schumann and Mendelssohn had contributed superb specimens to the repertory, but as of the 1860s those few new symphonies in the pipeline were dutiful graduation exercises or starchy prestige items, sleepwalking retreads all.

Even prior to his 1862 arrival in Vienna Brahms had been just about everybody’s prime candidate for the Prince Charming who would administer an awakening kiss to the slumbering symphonic beauty. But Brahms was a reluctant hero, to say the least. He wasn’t convinced that he had the requisite orchestral skill, and he was terrified lest his symphony might fail and make things even worse. He had begun one extended composition as a potential first symphony but re-purposed it as his first piano concerto—which was received with hisses at one of its early performances.

But he persevered. On July 1, 1862 his soul mate and muse Clara Schumann wrote to mutual friend Joseph Joachim: “Johannes sent me the other day—imagine the surprise!—the first movement of a symphony … the movement is full of wonderful beauties, and the themes are treated with a mastery which is becoming more and more characteristic of him.” But that was about it for a good while, until 1868 when Brahms sent Clara an ‘Alpine horn’ theme that was to become the glorious C-major sunburst that dispels the clouds in the First Symphony’s finale.

Then—no word. The symphony acquired a grandiloquent introduction and two relatively slender inner movements. But it remained maddeningly, frustratingly incomplete. The obstacle was the finale, which had to provide a worthy counterbalance to the magnificence of the first movement. Brahms wasn’t about to attempt the high-wire act of introducing a grand new symphony unless he was certain he had that elusive concluding movement.

It took until 1876, but he got there. The full gestation of Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 68 required 22 years. But it was worth it, and then some. Magnificent and game-changing, it made abundantly clear that the symphonic genre was by no means a dead letter, and in so doing opened the floodgates for a second golden age of the symphonic tradition—Dvořák, Mahler, Bruckner, Elgar. And Brahms himself: his Symphony No. 2 in D Major followed a year later.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

The 23-24 TRAILBLAZERS Season concludes with BRAHMS OBSESSIONS, on Saturday, May 4 at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, May 5 at 4 p.m. at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Tickets are $45 to $90 and $20 for students 25 and under, and include a free 30-minute pre-concert talk starting one hour before the performance. Buy tickets online or call or visit the Lesher Center Ticket Office at 925.943.7469, Wed – Sun, 12:00 noon to 6:00 p.m.