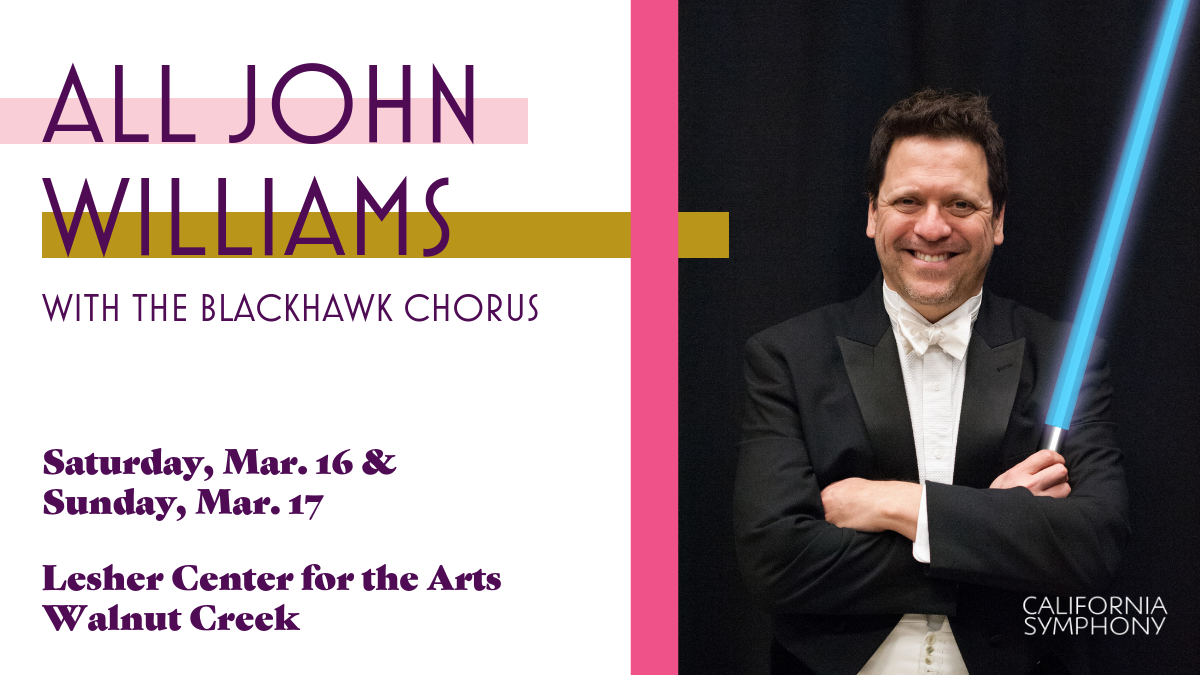

PROGRAM: ALL JOHN WILLIAMS with the Blackhawk Chorus

Saturday, March 16 at 8PM and Sunday, March 17 at 4PM, at the Lesher Center in Walnut Creek

- Olympic Fanfare and Theme

- Superman March from Superman

- Harry’s Wondrous World from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

- Theme from Schindler’s List

- Adventure’s on Earth from E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial

- The Cowboys Overture

- Hymn to the Fallen from Saving Private Ryan

- Battle of the Heroes from Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith

- Duel of the Fates from Star Wars: The Phantom Menace for Orchestra

- Main Title from Star Wars Suite for Orchestra

- Imperial March from Star Wars Suite for Orchestra

It’s one of history’s little ironies that movie music began in the silent era. In those days producers would send out scores for the accompanists—pianists, organists, or even full orchestras—whose primary job was to mask projection noises while also providing support for the onscreen action. Some ‘scores’ were just collections of generic figures and extracts from popular symphonies and operas. Others were fully-composed works employing leitmotifs, or ‘signature tunes’ that associated themselves with characters, situations, or places, and that evolved right along with the dramatic arc of the movie. The best of them could transform a silent film into a symphonic poem with images.

It was those silent film scores that evolved into what we now think of as movie music. But that didn’t happen right away. Musical scoring was rare in the early silent films, partly due to technical limitations, but also due to a general discomfort with apparently disembodied music emerging from the theater’s speakers. A fair number of landmark moments of early sound film occur in eerie silence—our first look at Boris Karloff as the Frankenstein monster or Bela Lugosi’s Count Dracula rising from his coffin, just to name two.

In 1933 the pioneering film composer Max Steiner created the score to King Kong and established movie music for generations to come. King Kong does it all—leitmotifs, surging accompaniment to action sequences, and touching love music, all expressed in a late Romantic style redolent of Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, and Richard Wagner. For better or worse, the Steiner idiom became the Hollywood norm, employed by such masters as Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Franz Waxman. “Who’s going up those stairs to die, me or Max Steiner?” quipped Bette Davis while filming the conclusion of Dark Victory.

In the post-War years audiences heard less Richard Strauss and more naturalism. An innovator emerged: Bernard Herrmann, who cut his teeth on Citizen Kane, scored a host of science-fiction films, then entered a fertile partnership with Alfred Hitchcock. Herrmann chose his materials, including the instrumentation, to match the needs of the film. A Herrmann score might feature strings alone, organs, or even electronics, but not a symphonic orchestra unless it fit the movie, as in Hitchcock’s masterful Vertigo. Herrmann’s exploration of non-orchestral sounds impacted film composers throughout the 1950s and 1960s—consider the bluegrass of Bonnie and Clyde or the synthesized abstractions of Forbidden Planet.

By the early 1970s film scoring had become highly eclectic, but perhaps less effective. Too many scores were mashups of popular songs or styles, apparently aiming mostly for the Best Song Oscar rather than a full theatrical experience.

That’s when John Williams—formerly the ‘Johnny Williams’ who wrote TV music and arrangements for Henry Mancini—entered international consciousness as the leading film composer of the later 20th century. After several fine scores for Irwin Allen’s The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno, and especially the 1972 John Wayne film The Cowboys, Williams struck gold with Steven Spielberg’s masterful Jaws. While Williams’s ominous two-note shark leitmotif has become a musical semaphore for anything ominous or threatening, the entire score is remarkable for its support of the now-classic thriller’s charged drama.

If Jaws made Williams into a major film composer, Star Wars catapulted him into film immortality. Recognizing that George Lucas’s joyous space opera harked back to the derring-do exuberance of pulp science fiction, Williams reached back into Hollywood’s past and resurrected the Max Steiner-style opulent film score, played by a massive symphony orchestra and written in the language of the late Romantic and early 20th century. By now the Hollywood studios had disbanded their crackerjack studio orchestras, so Williams made spectacular use of the London Symphony Orchestra for the soundtrack recording, establishing a trend of employing one of the world’s major orchestras for film. The original Star Wars score is so evocative that one can have a delightful time watching the film dialog-free, with just the musical score, just as one might with Korngold’s The Adventures of Robin Hood or Waxman’s The Bride of Frankenstein.

The Star Wars franchise has engendered a number of superb Williams scores: Revenge of the Sith, The Phantom Menace, and so on. With such an enviable track record it’s not surprising that Williams became the go-to composer for adventure and fantasy movies, such as Superman with its larger-than-life score that could almost stand alone as a symphonic poem à la Richard Strauss.

But there is another side to Williams’s work, one best exemplified by his daring and unconventional scores for some of Steven Spielberg’s most intimate and personally-felt movies. For Schindler’s List Williams created a supreme masterpiece of film scoring. Consider his use of a children’s song during the harrowing liquidation of the Krakow ghetto, the wailing violin that accompanies the chilling scenes in Auschwitz, or the warm dignified compassion of his main theme. For E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial Williams mixed electronics with full orchestra in a score that practically leaps out of the screen: who can ever forget the exultation of the flying bicycle scenes or the titanic ending as the departing space ship traces a rainbow over the night sky?

Saving Private Ryan was one of Spielberg’s most honored films, and it elicited one of Williams’s finest scores, a hymn of consolation and bittersweet remembrance. Ever flexible, Williams had no difficulty eliciting childhood magic in the scintillating fantasy of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, a score not that not only matches the delicious whimsy of the story but also evokes its sense of yearning.

John Williams has announced that he will retire from film composing after one more Star Wars film, due to be released in December 2019. As with Max Steiner, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Franz Waxman before him, he defined an entire era and continues to influence film composers present and no doubt future. His achievements stand as movie music at its very best, sure to last as long as there are people who love movies and their music.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony.

ALL JOHN WILLIAMS takes place on Saturday, Mar. 16 at 8 PM and Sunday, Mar. 17 at 4 PM at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek.