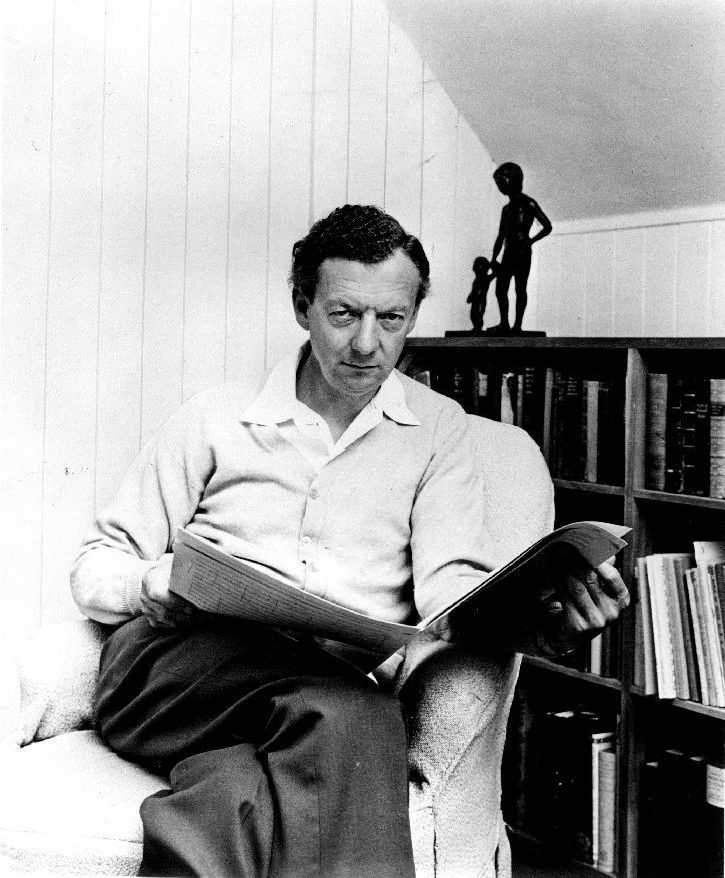

Benjamin Britten (1913—1976)

Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings

Benjamin Britten photographed by Hans Wild for High Fidelity magazine (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Benjamin Britten’s prodigious compositional output was not matched by an equally robust physical constitution. He suffered through any number of ailments, thus many of his finest works were conceived and composed during hospitalizations or retreats, while others were shaped by illnesses ranging from measles to flu to heart disease.

Britten’s 1943 Serenade for tenor, horn, and string orchestra provides a case in point. Written during an extended convalescence at the Grove Hospital in Tooting, South London, the work’s texts focus on night, sleep, and dreams; its worlds are moonlit woods, altered reality, and poetically-charged landscapes.

By definition any composition with text is a collaboration between composer and poet—living or deceased—but in the case of the Serenade two additional godparents were critical to the work’s gestation and, indeed, to its very existence. First up: tenor Peter Pears, Britten’s lifelong partner and muse, whose intelligence, musicality, and flexible voice serves as a leitmotif throughout Britten’s output, from the Serenade through Peter Grimes through Death in Venice. Britten wrote the Serenade with Pears’ voice in mind; it was the one vocal instrument he knew perfectly, in all of its strengths and quirks and quiddities. Pears sang the premiere of the Serenade in 1943 and also gave us the first recording in 1944—a performance that has held up well over the years even with the abundance of subsequent outings by any number of worthy musicians.

The second muse: horn player supreme Dennis Brain, only recently come to Britten’s attention as of 1943 and on the verge of a stunning career as a transformative giant of the instrument. Brain had asked Britten for a horn concerto, and the richly-layered and evocative Serenade was what he got. The sounds, textures, and idioms of the horn provide the Serenade’s foundational underpinning. Consider the work’s constant invocation of basic hunting-horn intervals such as the 4th and 5th, as well as its ability to conjure up images of night, fantasy, and (of course) hunting.

Britten structured the Serenade so as to bookend its six poems with a pair of horn solos featuring the natural, rather than modern valved, horn. There’s something a bit otherworldly about the natural horn, not only via the oddly askew pitch of those notes that lie outside its normal palette, but also in its distinctly organic, subtly raspy quality. For the movements with voice the horn player shifts to the modern instrument with its buttery tone quality and secure pitches, but the overall afflatus of the work is established by that opening unaccompanied natural horn movement, and all else that follows is clearly informed by that opening.

The Serenade has been one of Britten’s most popular works from the get-go, and with good reason; it is a gift that keeps on giving. No matter how many times you hear it, something fresh emerges on each hearing. A newcomer to the work might pay special attention to the end of one song and the beginning of the next, noting how adroitly Britten threads figures from one song to another, creating a seamless continuation from text to text, poet to poet, and mood to mood. But one needn’t listen analytically or critically; the music flows forth with seeming inevitability, its essential rightness consistent throughout, requiring only presence from the listener as its many, and quietly subtle, glories unfold.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

This is the final episode of Poetry in Motion, a three-part series, premiering FREE online at and on Walnut Creek Public Access TV over three consecutive Saturdays, May 8, 15 and 22. Filmed at Bay Area landmark the Oakland Scottish Rite Center, each 20- to 45-minute episode features music for string orchestra that uses poetry as a source of inspiration.