Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Boléro (1928)

Within two years of its premiere at the Paris Ópera with famed danseuse Ida Rubinstein, Boléro had been conducted by Piero Coppola, Willem Mengelberg, Serge Koussevitzky, Arturo Toscanini, and Ravel himself. Four years later it was the background to a Carole Lombard movie titled, not surprisingly, Bolero. It has popped up in arrangements and adaptations by Frank Zappa and Rufus Wainwright. It was the background music for a fight scene between Kirk and Spock in the original Star Trek series. It has been heard on Doctor Who. Bo Derek made memorable use of it, as did Olympic ice skaters Torvill and Dean. It has been praised, reviled, interpreted, and analyzed. It has earned a king’s ransom in royalties.

Boléro. Perhaps the best-known orchestral work of the 20th century, it knocked ‘em dead in its original 1928 ballet incarnation and has sailed on merrily (and orchestrally) ever since. Ravel fashioned his ubiquitous masterpiece to a disarmingly simple recipe: 1) place a languorous, almost serpentine melody over a hypnotically repetitive rhythm, then 2) repeat ad infinitem, providing each iteration with increasingly lavish and sonorous orchestration. Thus Boléro progresses from whisper-soft to Richter-scale volume levels within about fifteen minutes. Nothing else happens save a searing fanfare at the very end.

Despite various philosophical interpretations that have been layered on the work over the years, Ravel was quite straightforward about his brainchild. In 1931 he explained that: “[Boléro] constitutes an experiment in a very special and limited direction, and should not be suspected of aiming at achieving anything different from, or anything more than, it actually does achieve.”

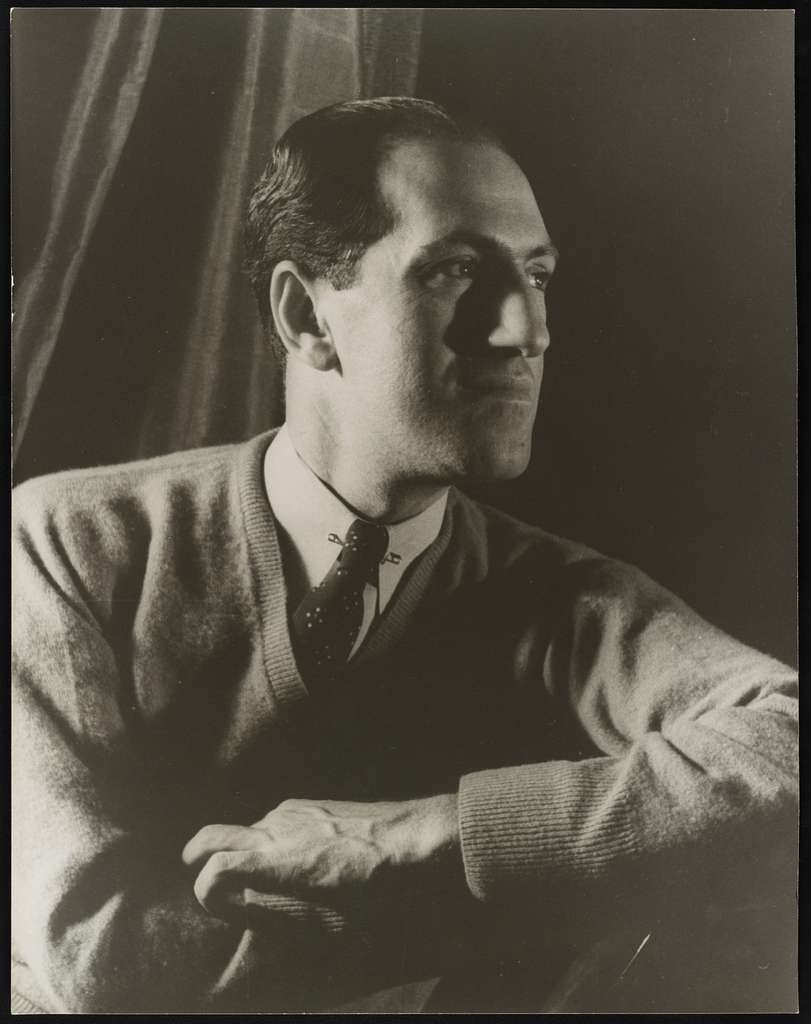

George Gershwin (1898–1937)

An American in Paris (1928)

Highbrow pundits never quite knew what to do about George Gershwin. That such a more or less self-taught Broadway tunesmith presumed to write ambitious concert works was annoying enough. That he was often boisterously successful with those same works was even more irritating. Some critics vented their umbrage via potshots at Gershwin’s perceived technical shortcomings. Others dismissed his works as mere passing fancies, such as the New York Evening Post’sOscar Thompson, who allowed that while An American in Paris might be all the rage circa 1928, “to conceive of a symphony audience listening to it with any degree of pleasure or patience twenty years from now, when whoopee is no longer even a word, is another matter.”

Raised patrician pinkies notwithstanding, conductors knew a good thing when they heard it and snapped the piece up. The 1929 midwestern premiere was led by no less than Fritz Reiner, soon to be followed by such luminaries as Artur Rodzinski, Alfredo Casella, and erstwhile San Francisco Symphony maestro Henry Hadley. Even Arturo Toscanini – nobody’s choice as an advocate for American music – turned in a whipcrack rendition with the NBC Symphony. The first studio recording, with Nathaniel Shilkret conducting the Victor Symphony and featuring an uncredited George Gershwin Himself on celesta, took place on February 4, 1929, less than two months after the New York premiere. Umpteen performances and recordings later, An American in Paris dances blithely towards its centennial, bedrock repertory, familiar and loved the world over. Far more than a mere Jazz Age travelogue, this quintessentially American symphonic poem unfolds with radiant vitality.

An American in Paris eschews formal symphonic development in favor of a loose episodic structure charting the adventures of an American tourist sampling the glories of Paris amidst fits of homesickness. The work’s most compelling features are its marvelous melodies – who isn’t enchanted by the central “blues” section with its wailing trumpet solo? – and its glittering orchestration, featuring that quacking quartet of Parisian taxi horns. “It’s not a Beethoven symphony, you know,” commented Gershwin, perhaps in reaction to elitist reservations about the work’s overriding joie de vivre. “If it pleases symphony audiences as a light, jolly piece, a series of impressions musically expressed, it succeeds.”

Modest Mussorgsky (1839–1881), orch. Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Pictures at an Exhibition (1874, orch. 1922)

The familiar claim that great art cannot be created by committee is sorely challenged by Pictures at an Exhibition, an undisputed masterpiece that may have been written by a single composer but involved the significant contributions of an artist (Viktor Hartmann), an editor (Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov), and a field of orchestrators (including Sir Henry Wood, Maurice Ravel, and Leopold Stokowski.)

Mussorgsky and the artist Viktor Hartmann met sometime around 1870. Their mutual devotion to nurturing a native Russian art encouraged the blossoming of a solid friendship, cut tragically short when Hartmann died in 1873 at the age of 39. A year later the influential critic Viktor Stasov helped to organize a showing of Hartmann’s works at the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts. That exhibition inspired Mussorgsky to plunge into the composition of Pictures at an Exhibition, originally titled Hartmann. Six weeks later the work was finished, although it was never to be performed publicly during Mussorgsky’s lifetime.

Music lovers are sometimes unaware that Mussorgsky wrote Pictures for solo piano; its history of orchestral transcription runs deep. In fact, the first known public performance of the work, in November 1891, was an abridged orchestration by Rimsky-Korsakov’s student Mikhail Tushmalov. Since then, approximately thirty orchestral transcriptions have been made of Pictures at an Exhibition.

Maurice Ravel’s masterful 1922 orchestration has become the de facto standard. Despite his fastidious disdain for Mussorgsky’s crudity, Ravel was a bonafide Russophile who could not help but respond to Pictures’s kaleidoscopic imagery. The celebrated result seamlessly blends two contrasting cultures in a milestone of orchestral writing.

Pictures at an Exhibition charts the course of visitors strolling through a gallery of Hartmann’s various paintings, sketches, and architectural fantasies. A Promenade theme acts as a musical museum guide, accompanying us from picture to picture as make our way along. It all culminates with Hartmann’s architectural design for The Great Gate of Kiev, originally intended for a civic competition. The gate itself was never built, but it lives on in Mussorgsky’s powerful portrait.

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

The 25-26 Season begins with PICTURES FROM PARIS on Saturday, September 27 at 7:30 p.m. and Sunday, September 28 at 4 p.m. at the Lesher Center for the Arts in Walnut Creek. Single tickets start at $50 and at $25 for students 25 and under, and include a free 30-minute pre-concert talk starting one hour before the performance. Buy tickets online or call or visit the Lesher Center Ticket Office at 925.943.7469, Wed – Sun, 12:00 noon to 6:00 p.m.