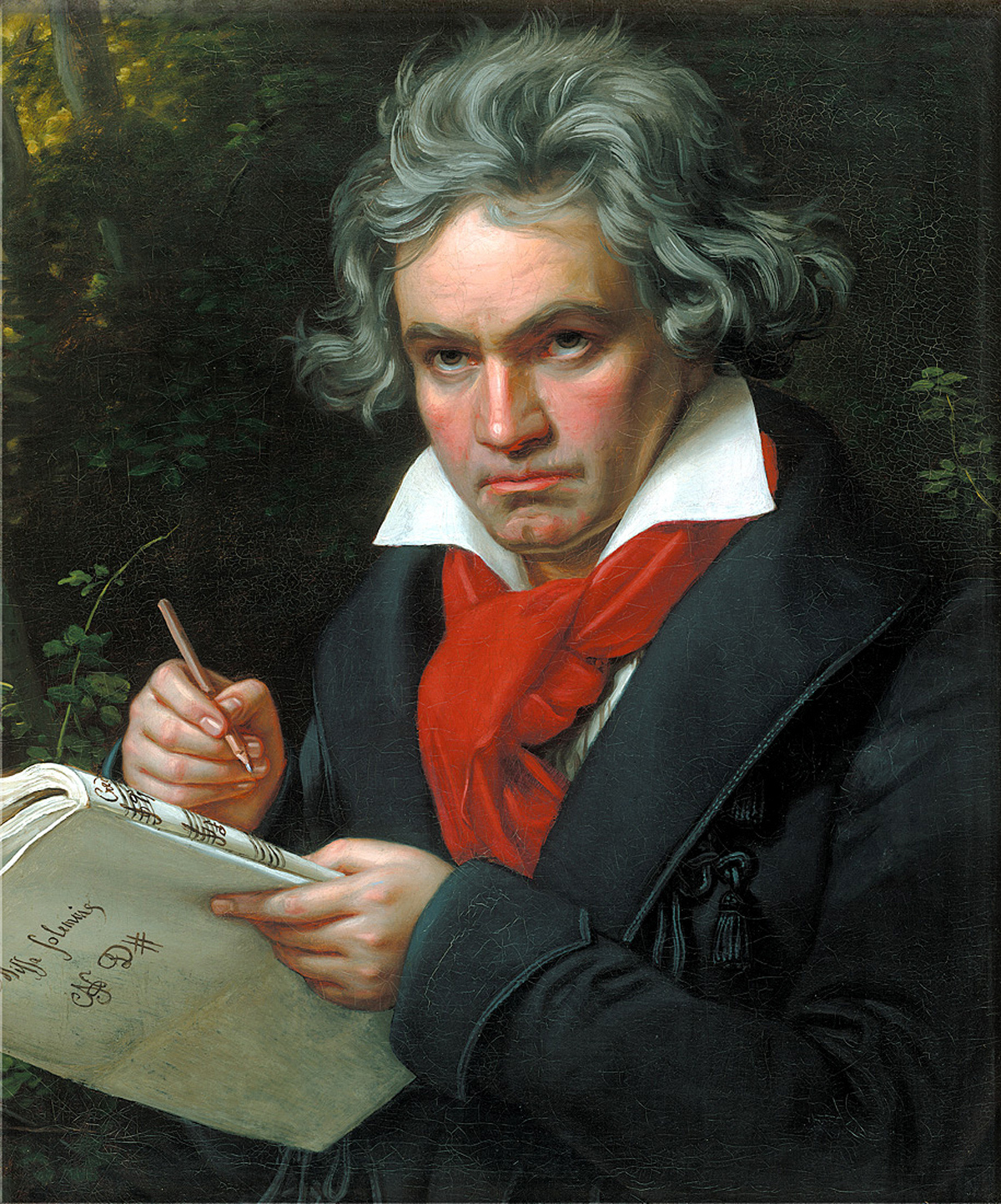

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827)

The Beethoven Piano Sonatas

The Beethoven Piano Sonatas

Nobody ever gets accused of bad taste for programming Beethoven piano sonatas. They are bedrock works after all, foundational to every pianist’s upbringing and subsequent career. The subject of books upon articles upon treatises upon essays upon program notes, they have been sliced, diced, dissected, disassembled, and discussed. They’ve been remixed and repurposed, adapted, redacted, and co-opted. Dubious theories have been floated and torpedoed, amusing origin stories have been concocted, fanciful nicknames have been bestowed. Once in a blue moon some grump gripes that maybe they aren’t really all that good, that they’re overrated, that they’ve unfairly eclipsed worthwhile contemporary sonatas by such as Ferdinand Ries or Johann Nepomuk Hummel or Carl Maria von Weber.

But pianists just keep on playing them, studios keep on recording them, and audiences keep on digging them. That’s with good reason. The 32 (give or take a few) Beethoven piano sonatas are wonderful and challenging, and given a halfway decent performance, invariably effective in concert. They are the sonatas of not only a master composer, but a master pianist: they live in the instrument, deeply idiomatic and imbued with the sheer physicality of hands on keyboard and feet on pedals.

Beethoven’s career is typically trisected into early, middle, and late periods, which the piano sonatas illustrate to perfection. On this program, the powerful middle-period “Waldstein” sonata in C Major of 1804 is coupled with a masterpiece of Beethoven’s later years, the lyrical yet complex sonata in E Major of 1820.

Piano Sonata No. 21 in C Major, Op. 53 (Waldstein)

Hereditary aristocrats aren’t generally known for financial discipline, and the nabobs of Enlightenment Austria were no exception. During the post-Napoleonic recession, some doofuses even sold off their estates to sustain their lavish Vienna lifestyles, apparently oblivious of the inevitable consequences. One hears stories of duchess-this or prince-that doing the after-dinner dishes in a stripped-bare palace kitchen, the roof leaking and creditors hammering at the door. Ah, karma.

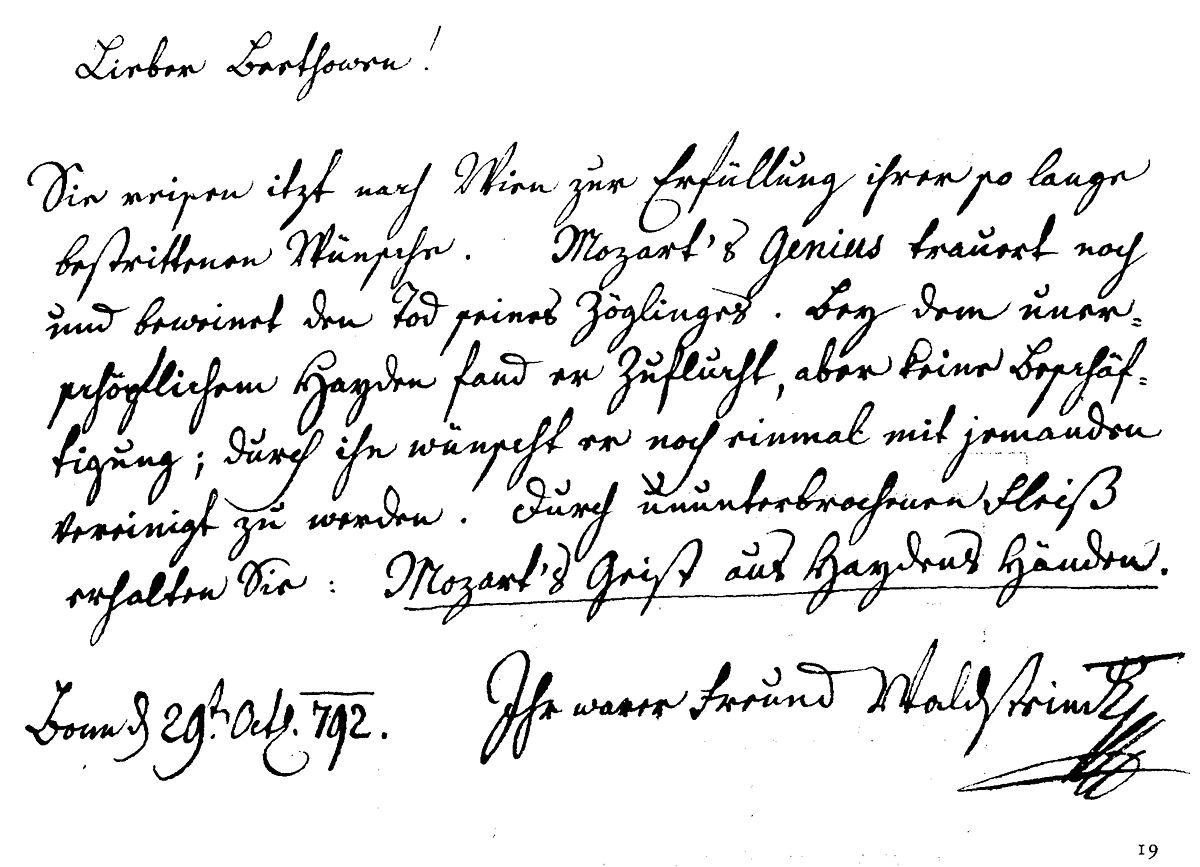

Cue Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein, born to stupendous wealth in 1762 and dead in a shelter for the destitute in 1823. He squandered both his and his wife’s estates on the financing for a private military regiment that seems to have done little beyond putting out a fire in a biscuit bakery. He followed up with a series of irresponsible investments that vaporized what wisps of his boodle yet remained. But in his affluent earlier days he gifted posterity via his patronage of the young Beethoven; it was Waldstein, in fact, who sponsored Beethoven’s relocation from provincial Bonn to big-apple Vienna in 1792. And it was Waldstein to whom Beethoven dedicated the magisterial C Major Piano Sonata, Opus 53.

Cue Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein, born to stupendous wealth in 1762 and dead in a shelter for the destitute in 1823. He squandered both his and his wife’s estates on the financing for a private military regiment that seems to have done little beyond putting out a fire in a biscuit bakery. He followed up with a series of irresponsible investments that vaporized what wisps of his boodle yet remained. But in his affluent earlier days he gifted posterity via his patronage of the young Beethoven; it was Waldstein, in fact, who sponsored Beethoven’s relocation from provincial Bonn to big-apple Vienna in 1792. And it was Waldstein to whom Beethoven dedicated the magisterial C Major Piano Sonata, Opus 53.

An entry from Beethoven’s friendship book penned by Count Waldstein reads “Dear Beethoven! You go to realise a long-desired wish: the genius of Mozart is still in mourning and weeps for the death of its disciple. (…) By incessant application, receive Mozart’s spirit from Haydn’s hands.”

The Waldstein is a symphony masquerading as a piano sonata. Painted on a panoramic canvas and shot through with the supercharged energy characteristic of such glorious mid-period works as the Kreutzer violin sonata, the Waldstein is a concert work of uncommon effectiveness, even by Beethovenian standards. The first movement, marked Allegro con brio, elicits a steam-engine affect in its surging rhythms and headlong forward momentum. There’s no ‘slow movement’ in the usual sense, but an Adagio molto “introduction” that provides a moment of respite before launching into the utterly magical rondo finale, featuring an innovative use of the ‘damper’ pedal that creates a shimmering acoustic nimbus around the main reprise, repeats of which are contrasted with propulsively athletic episodes, the whole capped off by a madcap coda.

Piano Sonata No. 30 in E Major, Op. 109

Beethoven’s final three piano sonatas—Opp. 109, 110, and 111—earned him a publishing fee of 90 ducats, a goodly sum to be sure, but trifling considering the prestige those sonatas have acquired over the two centuries since Beethoven’s April 1820 contract with publisher Adolph Martin Schlesinger. Their agreement specified a deadline of three months hence, a target that went woefully unmet as the last sonata Op. 111 did not appear in print until 1823. However, Beethoven came quite close to meeting the deadline with Op. 109, which he declared as ready for publication in September of 1820. But Beethoven’s notoriously sloppy manuscripts resulted in galley proofs riddled with errors, and his ill health at the time prevented him from making adequate corrections. The result was an altogether unsatisfactory first edition in November 1821.

Those last three sonatas were worth waiting for. Milestones in the evolution of the piano repertory, each is in its own way a re-thinking and re-fashioning of the entire concept of a piano sonata, taking the genre on a journey far beyond its humble beginnings in the Italian Baroque as a musical aperitif.

Thus Opus 109 in E Major. The fantasy-like opening movement bears a distinctly improvisatory quality due to its numerous tempo and mood changes. The second-place Prestissimo is a grand example of a scherzo, that turbocharged minuet-on-steroids that Beethoven had made so uniquely his own since the early days. Disruptive and abrupt, it shatters the lyricism of the first movement with its minor mode, outbursts of anger, and distinctly manic personality.

After a much-needed pause, a sublime series of variations commences. The term “variations” tends to elicit notions of relatively easy listening, as some catchy little tune is elaborated in various ways, usually by piling on ornamentation or keyboard figurations. But not here. The variations progressively simplify, rather than elaborate, the opening melody, as we become increasingly aware of the underlying skeleton of the theme, over time discovering its essence, as it were.

Ace commentator Sir Donald Francis Tovey’s astute advice to listeners regarding Opus 109 dates from 1951 but remains as trenchant and valuable as ever: “We attend to what reaches our senses,” he wrote in his notes on this sonata, “and we allow the sum of our experience to tell us more in its own good time.”

Program Annotator Scott Foglesong is the Chair of Musicianship and Music Theory at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, and a Contributing Writer and Lecturer for the San Francisco Symphony. He also leads the California Symphony’s ground-breaking music education course for adults Fresh Look: The Symphony Exposed.

Hear Adam Golka masterfully bring to life Beethoven’s Waldstein and Piano Sonata No. 30 at Bravo for #Beethoven250. Join us as we kick off our first ever virtual concert series Second Saturdays @ California Symphony, FREE to watch online from the comfort of your couch. Learn more here.

Hear Adam Golka masterfully bring to life Beethoven’s Waldstein and Piano Sonata No. 30 at Bravo for #Beethoven250. Join us as we kick off our first ever virtual concert series Second Saturdays @ California Symphony, FREE to watch online from the comfort of your couch. Learn more here.